Shortly after taking over U.S. sales of BMW automobiles from

independent distributor Max Hoffman in 1975, BMW of North America

initiated the process to do the same for the motorcycle side of the business.

BMW had been exporting motorcycles to the U.S. since 1950, less than

two years after production had resumed in Munich following the

destruction of World War II. At first, bikes were ordered directly by

dealers whose relationship with BMW predated the war, like Oscar

Liebmann, whose New Jersey-based AMOL Precision became the first

official BMW motorcycle dealer in the U.S. in 1950. By the end of that

year, however, the right to distribute BMW’s motorcycles in this

market was assigned to the V. (for Victor) Harasty organization.

Four years later, that privilege was transferred to the Butler &

Smith Trading Company. (Contrary to assumptions, the name of the firm

referred not to its founders but to the intersection in Brooklyn where

the company was located. Butler & Smith first imported NSU

motorcycles from Germany, then Lambretta scooters from Italy.)

On February 19, 1954, Butler & Smith president Alfred Bondy wrote

a letter to inform NSU and BMW motorcycle dealers that Butler &

Smith was BMW’s official U.S. importer. Bondy expressed his desire

that BMW dealers should continue with the new distributor, which would

“combine Germany’s two most prominent brands which are world renowned

for their workmanship and performance.” Bondy also stated that “The

first BMW motorcycles will arrive in a few days. A large quantity of

BMW parts is on order from the factory, and we hope that our

reputation for fast and complete NSU parts service will soon apply to

our BMW parts service.”

Initially, Butler & Smith would handle operations on the East

Coast, with West Coast distribution delegated to the Flanders Company

of Pasadena, California. In 1969, Butler & Smith took over

distribution for the entire U.S., and in May 1970 established a new

headquarters and import center in Norwood, New Jersey.

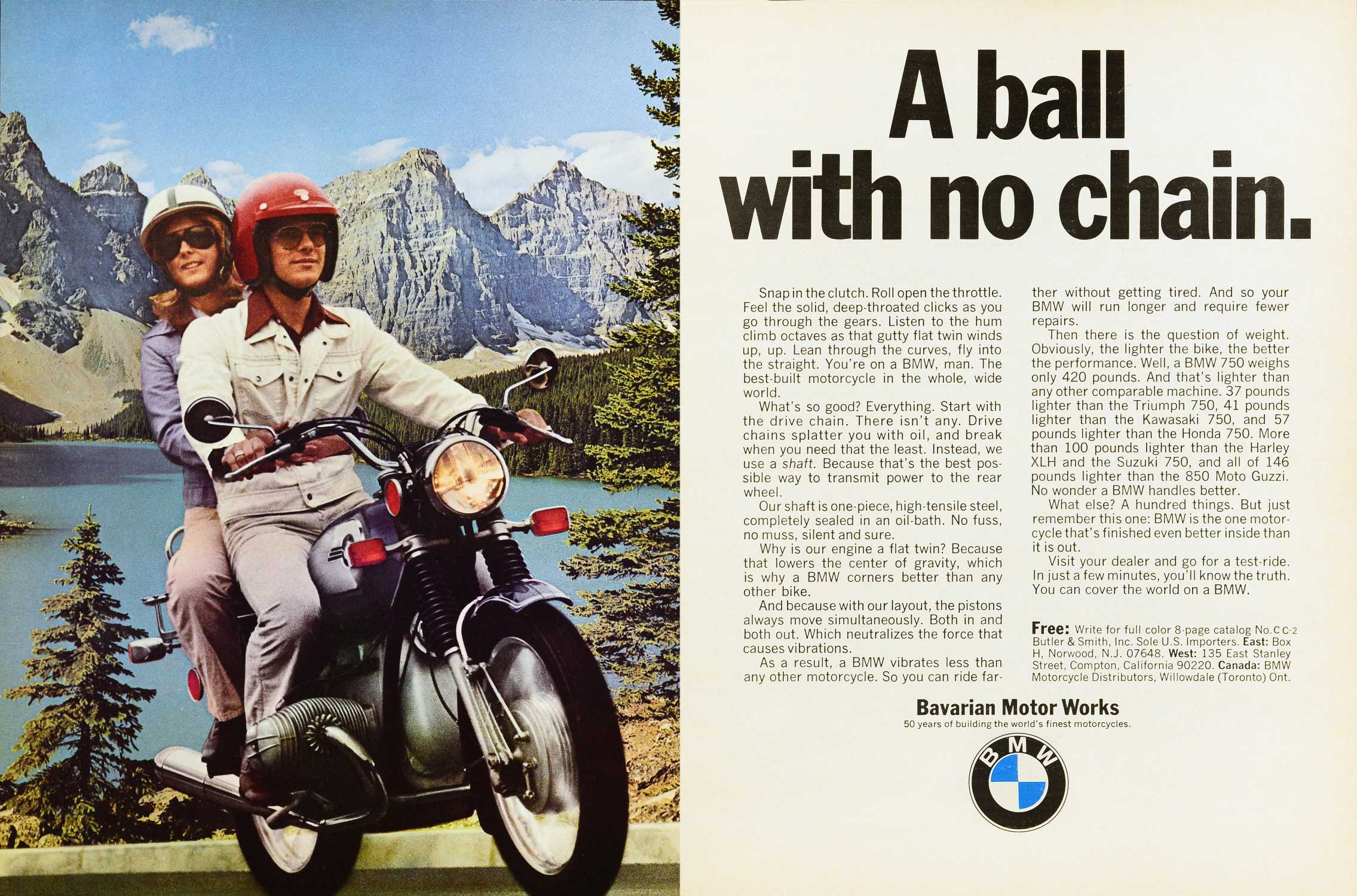

Even prior to that move, Butler & Smith had ensured that BMW

built motorcycles suited to the needs and tastes of U.S. riders, most

of whom used bikes like the R 50 and R 69 for long-distance touring.

Their suitability for that purpose had been firmly established in

1958, when Ohio dealer John Penton rode his 600cc R 69 from New York

to Los Angeles in 52 hours, 11 minutes, setting a new record and

gaining great publicity for the reliability of BMW motorcycles.

(Penton was an accomplished off-road rider, and he’d ride a

factory-backed R 27 single in the 1962 International Six Days Trial,

winning a silver medal despite a few bad crashes.) Thanks to Butler

& Smith, BMW motorcycles could be ordered in the U.S. with options

like dual seats, higher handlebars, and accessories like saddlebags,

fairings, and the side stands preferred by Americans over the standard

center stand. Later, Butler & Smith would offer aftermarket

equipment including Krauser luggage, Luftmeister fairings, and

Continental or Metzeler tires.

BMW built sporty models as well as touring bikes, of course, and

Butler & Smith went racing to promote them. The firm became

especially active on the racetrack following the move to New Jersey,

which likely coincided with the ascension of Dr. Peter Adams to the

leadership of the Butler & Smith firm. Adams was the son of Butler

& Smith owner Irwin Adams, who may have founded or purchased it

with Bondy in 1949 but who had in any case become its sole owner by 1970.

Adams formed a technologically sophisticated race team led by Udo

Gietl and Todd Schuster, both of whom were innovative fabricators and

technicians. The team got off to a fine start in 1971, campaigning a

thoroughly exotic 750cc machine in the American Motorcycle

Association’s Formula 750 class with riders Reg Pridmore and Gary

Fisher. Five years later, the Butler & Smith team switched to the

R 90 S, and its extensively modified bikes finished 1-2 in the very

first AMA Superbike championship, with Reg Pridmore taking the crown

over teammate Steve McLaughlin.

The elation of that championship would be short-lived, at least where

Butler & Smith was concerned. Having taken over U.S. automobile

sales and distribution from Max Hoffman in March 1975, BMW of North

America was looking to do the same for its motorcycles. Dr. Adams

resisted the takeover, and in 1978 filed suit to retain his

distributorship. BMW of North America prevailed in September 1980, and

that October saw the company take possession of the Butler & Smith

operation at Walnut and Hudson streets in Norwood, New Jersey.

The new division was led by vice-president Jean-Pierre Bailby, who’d

come to North America from BMW France. Joseph Salluzzo served as

national sales manager, with Rolf Kettler as marketing manager. Below

them, many of the motorcycle division’s employees were retained from

Butler & Smith, at least temporarily.

“At that point, all of the employees in sales, parts, and service

were Butler & Smith employees, wondering what happens next,” said

Rob Mitchell. “Eventually, people from BMW NA started filling some

positions. I came about six months later to head up advertising and

promotion, taking over from Rolf Kettler, who’d been sent over

temporarily from Germany. I’d been in sales training, and I got hired

because I was the only person at NA who rode motorcycles. It was a

real trial-by-fire.”

Mitchell worked out of an office in Norwood for the next two years,

until the motorcycle division moved to BMW of North America’s

headquarters in Montvale. In the interim, BMW NA began modernizing

operations for sales and distribution, financing, and technical

training. Imposing new standards allowed BMW to cut the number of U.S.

dealers by half, from around 300 to 150. “Like Hoffman, Butler &

Smith would sign you up as a dealer if you purchased $500 worth of

parts and a [BMW] sign,” Mitchell said. “I visited one dealer in

upstate New York that was in an extension of his house, and which had

a dirt floor in the workshop. Once BMW NA put certain operating

requirements for corporate signage, inventory, facilities, and

technical training—all the normal dealership stuff—dealers like that,

who weren’t willing to step up and make the investment, fell away.”

Replacing Butler & Smith with a modern, efficient sales

subsidiary yielded tangible benefits, Mitchell said. “Back in the old

days, you’d pick up the telephone and order a bike from Butler &

Smith. Now you had a modern business culture for ordering bikes and

parts, signing up for technical training, all of that. Some dealers

were upset that they could no longer continue the way they had before,

but those who stayed on found they could offer a lot more to

customers. And the customers got way better support, too. It’s much

better to go into a dealer and see dozens of new bikes rather than

just one, plus accessories and people anxious to help you.”

As it had with the cars, BMW of North America was hoping to increase

sales of BMW motorcycles in the U.S., and to take advantage of

motorcycles’ burgeoning popularity in this country. (That phenomenon

was due largely to the Japanese manufacturers, who marketed their

lightweight motorcycles to young people as an alternative to cars, and

as a “fun” alternative to heavyweight American machines.) Although

hard data isn’t available for the years immediately before and after

the transition, documents within the BMW Archive record declining

export volumes to the U.S. in the mid 1970s: 10,553 units in 1974;

9,256 units in 1975; and 7,539 units in 1976. Presumably, imports

declined further as the decade wore on. Mitchell doesn’t know the

exact figures, but believes that Butler & Smith was selling

perhaps 2,500 motorcycles per year by the time BMW of North America

took over sales and distribution in 1980.

In 1985, the earliest year for which BMW NA data is available, the

company sold 5,597 motorcycles in the U.S., followed by 6,078 in 1986.

That number represented barely one percent of new motorcycles sold in

the U.S. per annum, but it was a significant improvement nonetheless.

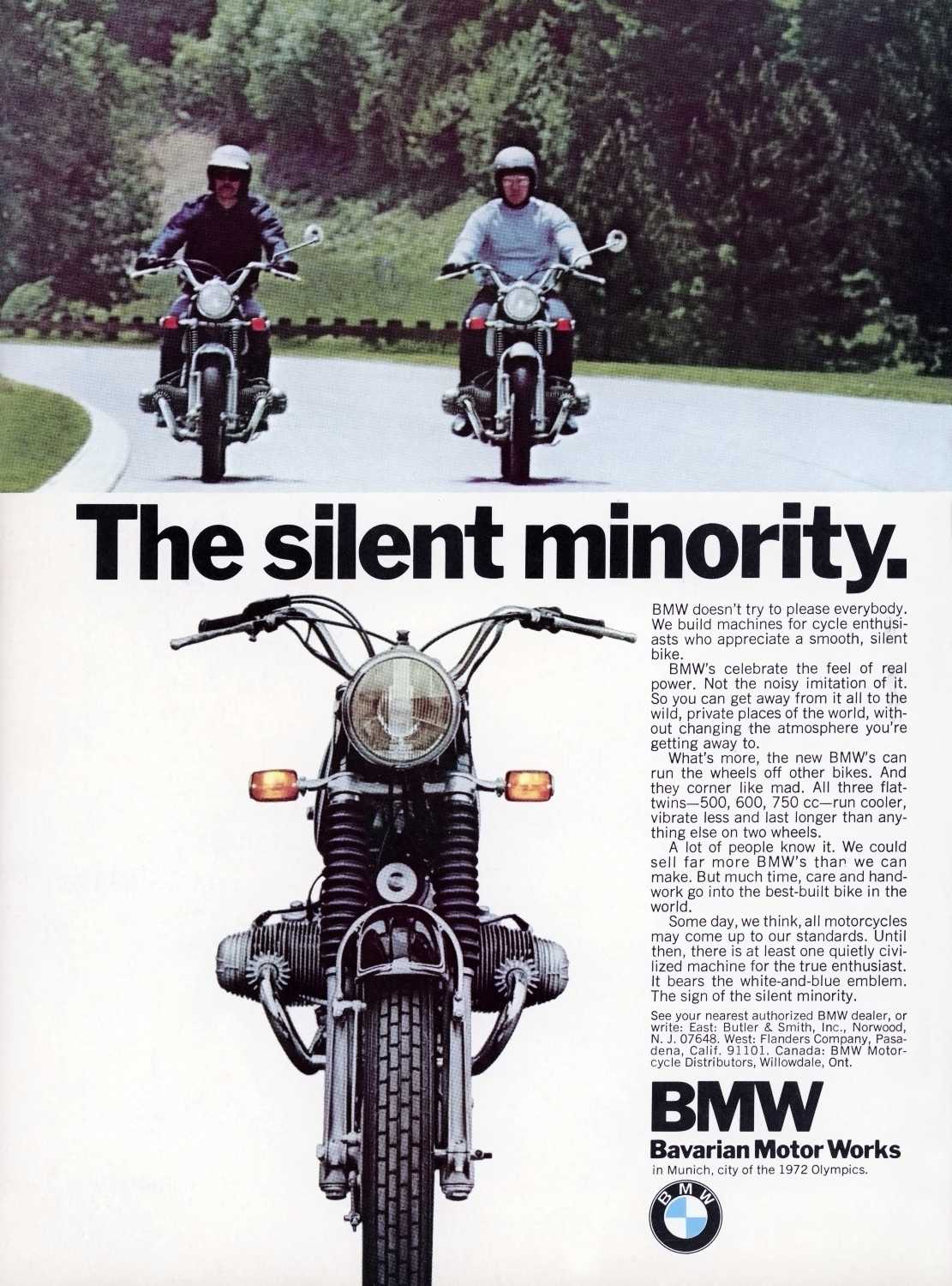

A new ad campaign helped. After an agency review, BMW’s motorcycle

account was moved to Ammirati & Puris, which had created “The

Ultimate Driving Machine” tagline that resonated so strongly with car

buyers. For the motorcycles, Ammirati & Puris came up with another

memorable slogan, “The Legendary Motorcycles of Germany,” which

emphasized the company’s heritage at a time when BMW’s performance was

somewhat tepid compared to that of the Japanese and Italian marques.

Ammirati & Puris placed ads in the Wall Street Journal and Esquire

magazine, hoping to reach upscale customers. This didn’t always work,

Mitchell said. “Motorcyclists are grass-roots people, and prestige

isn’t the biggest thing. It’s a very different group than the car people.”

More important, Mitchell said, was ensuring that BMW NA maintained a

press fleet of new motorcycles, and staged press launches to ensure

that new models were reviewed in motorcycle magazines. Those new

models would themselves help BMW NA succeed, especially after the R 80

G/S caught on with adventure-touring riders following its 1980

introduction. “What started as an oddity—an 800cc, 400-pound dirt

bike—became the most important segment, but it took probably ten years

to really take off.”

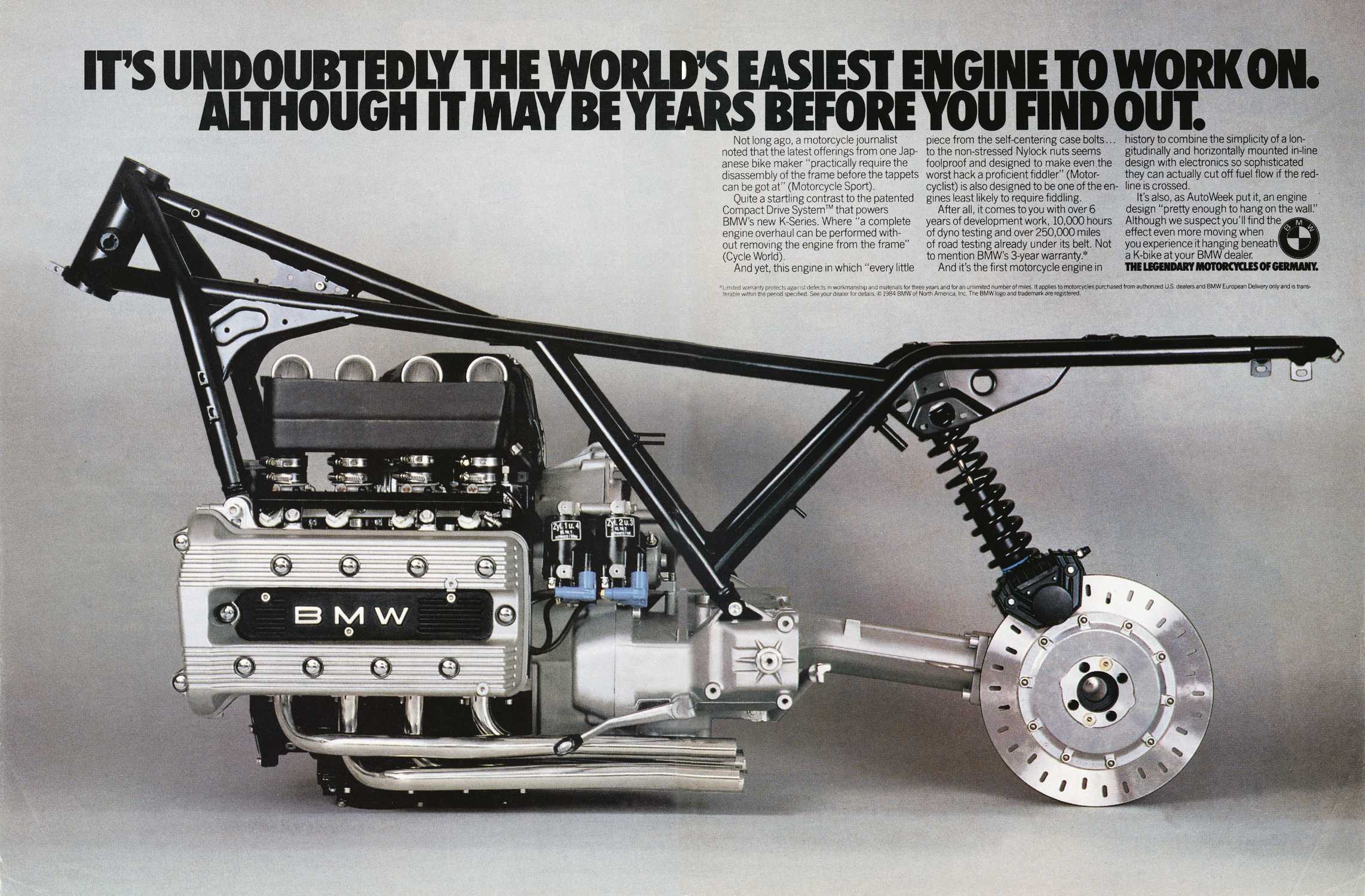

In late 1983, BMW would enter another crucial segment, supplementing

its longstanding boxer twin lineup with all-new K bikes powered by

water-cooled three- and four-cylinder engines. “Even longtime boxer

owners seemed genuinely excited by the K bikes,” Mitchell said. “There

was clearly room for both within BMW.”

Today, BMW Motorrad USA offers a full range of motorcycles, from the

entry-level G 310 R and GS to the Superbike-spec M 1000 RR, with all

manner of touring, heritage, urban, and adventure bikes in between. A

wide variety of engines is available, from singles to inline sixes,

plus inline fours, Boxer and parallel twins, and even battery-powered scooters.

BMW Motorrad’s factories in Berlin and elsewhere around the world are

busier than ever, turning out 209,257 bikes in 2023. Of those, 24,176

went to customers in Germany and 21,668 to France, while 17,017 were

delivered to customers in the U.S., BMW Motorrad’s third-largest

motorcycle market worldwide. That number constitutes only a small

fraction of the half-million-plus motorcycles sold in the U.S. last

year, but volume isn’t everything. BMW riders have long been among the

industry’s most enthusiastic riders, especially when it comes to

putting serious mileage on their machines. Just like John Penton’s R

69 in 1959, BMW motorcycles continue to carry their riders quickly and

reliably from coast to coast…and beyond.

—end—