To the extent that historical press releases reference BMW Manufacturing Co., LLC as the manufacturer of certain X model vehicles, the referenced vehicles are manufactured in South Carolina with a combination of U.S. origin and imported parts and components.

PressClub USA · Article.

BMW NA 50th Anniversary | 50 Stories for 50 Years Chapter 4: “BMW of North America: Ready for Business”

Mon Jan 27 17:35:00 CET 2025 Press Release

Upon taking his seat on the BMW board of management, Bob Lutz began replacing BMW’s independent distributors with wholly-owned sales subsidiaries, first in France in 1973, then in Belgium and Italy. The move would increase profit—on a per-car basis, the distributors had been earning vastly more than BMW itself—and it would also allow BMW to rationalize product planning and manufacturing. Equally important, it would allow BMW to unify its advertising and brand management for the first time in company history. “You can’t define the brand if you have individual distributors and individual companies makin

Press Contact.

Thomas Plucinsky

BMW Group

Tel: +1-201-307-3701

send an e-mail

Author.

Thomas Plucinsky

BMW Group

Related Links.

Upon taking his seat on the BMW board of management, Bob Lutz began replacing BMW’s independent distributors with wholly-owned sales subsidiaries, first in France in 1973, then in Belgium and Italy. The move would increase profit—on a per-car basis, the distributors had been earning vastly more than BMW itself—and it would also allow BMW to rationalize product planning and manufacturing. Equally important, it would allow BMW to unify its advertising and brand management for the first time in company history. “You can’t define the brand if you have individual distributors and individual companies making up their own minds how to advertise, how to position the car and so forth,” Lutz said.

Franchise laws in the US would make it difficult to extricate BMW from its unusually long contract with distributor Max Hoffman, but Lutz had good reason to sever the relationship. Hoffman’s representation was inadequate or even detrimental where customer service was concerned, and it had the potential to cause legal problems when Hoffman failed to approve warranty claims as required by law. An attorney retained by BMW, George Galland, had discovered as much himself when his 2002’s air pump stopped working and Hoffman refused to replace it under warranty. Hoffman was also neglecting to keep BMW apprised of the emissions-related regulations for which BMW was ultimately responsible for compliance, raising the specter of fines and penalties for the Munich carmaker.

To address the latter issue, Lutz established BMW of North America on June 12, 1973, with an office in New York City. (The office would later move to Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.) Led by former GM executive and BMW enthusiast John Plant, the office would deal with regulatory matters while providing BMW’s Munich-based executives with a base of operations during their visits to the US. As a legal entity, BMW of North America would be able to take over from Hoffman once Lutz managed to sever BMW’s relationship with its longtime US distributor. In the meantime, the office hoped to help Hoffman modernize his business and improve customer service.

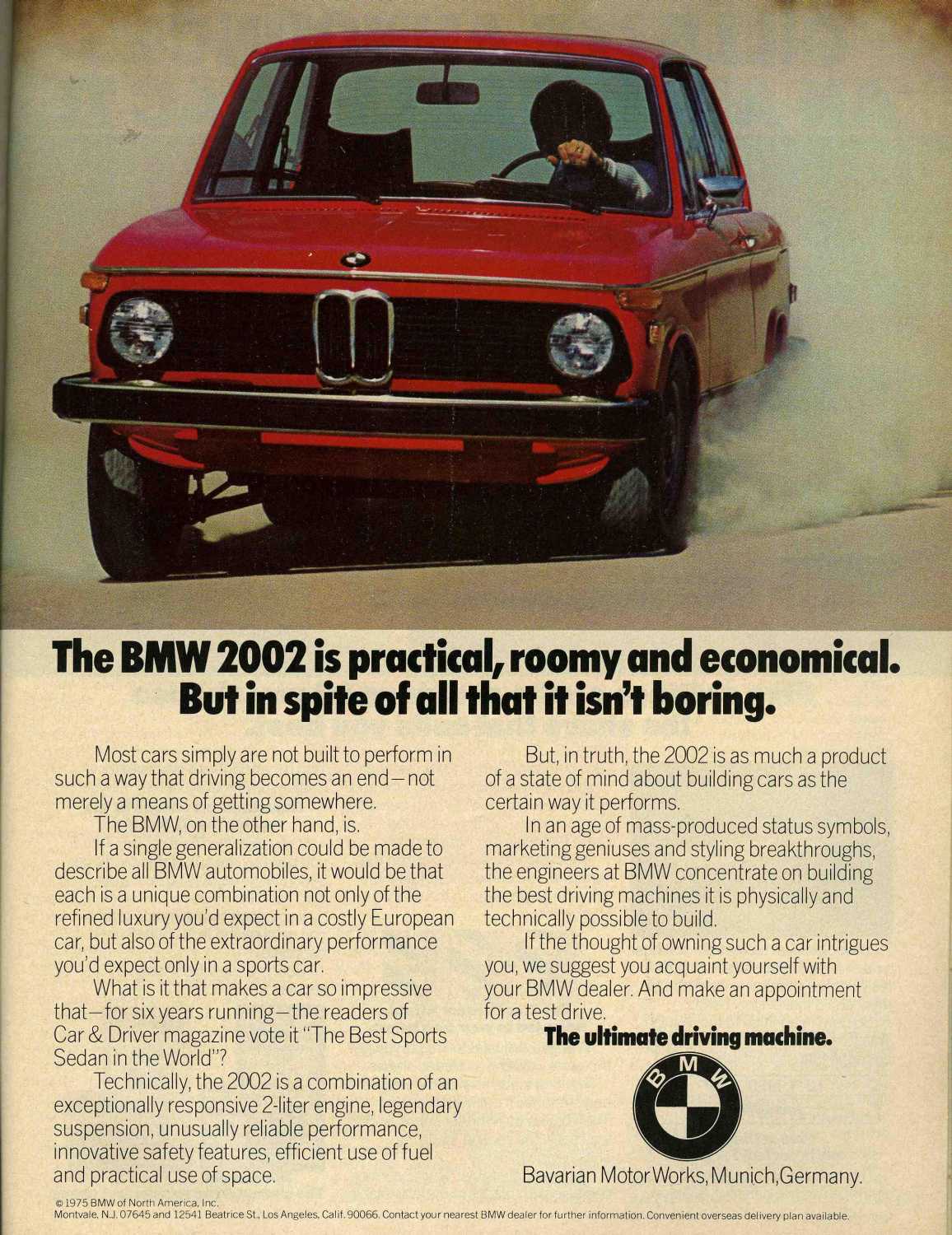

The US was already BMW’s largest export market thanks to the popularity of the 2002 among American enthusiasts, but Hoffman’s ordering process became more erratic than ever, causing problems for workers and management at BMW’s Munich plant. An entreaty from works council president Kurt Golda to majority shareholder Herbert Quandt seems to have been Hoffman’s last straw: On instructions from Quandt, BMW issued a notice of termination to the agreement on July 9, 1974, citing “serious commercial reasons.”

BMW attempted to create a joint distribution company in which Munich would hold 51% of shares and Hoffman the remainder, but Hoffman broke off negotiations and sued BMW in September. BMW countersued in both Munich and US federal court, citing the damage that had ensued from Hoffman’s business practices.

On March 14th 1975, BMW and Max Hoffman reached a settlement. BMW issued checks to Hoffman that totaled approximately $36 million to buy out his distributorship. The company also leased Hoffman’s existing facilities in New Jersey, Los Angeles, and elsewhere throughout the US. Finally, Hoffman asked and was given the opportunity to consult on design issues for North America, about which he’d long been passionate. Interestingly, this last point was not documented in the settlement agreement and it is unclear whether Hoffman ever did consult with BMW after the deal was signed.

By then, Lutz had left BMW, having departed on July 31, 1974 to become chairman of Ford of Europe. Though his tenure had been brief, he’d played a major role in modernizing BMW and ensuring its profitability for years to come.

On March 15, 1975, a company named BMW of North America was open for business, occupying what had been Hoffman Motors’ headquarters in Montvale, New Jersey.

The new national sales company was led by CEO John A. (Jack) Cook, who proved an inspired choice for the position. Born in Canada, Cook had worked for General Motors and Volkswagen in his home country and Australia before joining Volkswagen of America in 1969 as VP in charge of Porsche-Audi. In that role, Cook had met BMW sales manager Hans-Erdmann Schönbeck—Lutz’s successor as board member for sales—who hired him to head BMW of North America.

“Jack was a terrific leader,” said Tom McGurn, who joined BMW NA at its founding and served as its first public relations manager. “He had a relatively young staff who were doing probably the biggest things in their career at that time. He had a great balance between giving you enough freedom and providing a safety net if you needed one. His attitude was, ‘It didn’t work out. What did you learn from it? What would you do next time? Go forth and do good things.’ He was really a good guy.”

Cook met the automotive press for the first time in March 1975, telling journalists he expected to sell 18,000 cars that year. By the time 1975 was out, BMW had sold three thousand more cars than Cook had predicted. It was a great start, but Cook was just getting started. BMW NA had inherited a passionate customer base, but brand recognition was low among the public at large. Surveys showed that fewer than one-quarter of Americans had even heard of BMW, and those that had usually thought the acronym stood for British Motor Works, not Bavarian.

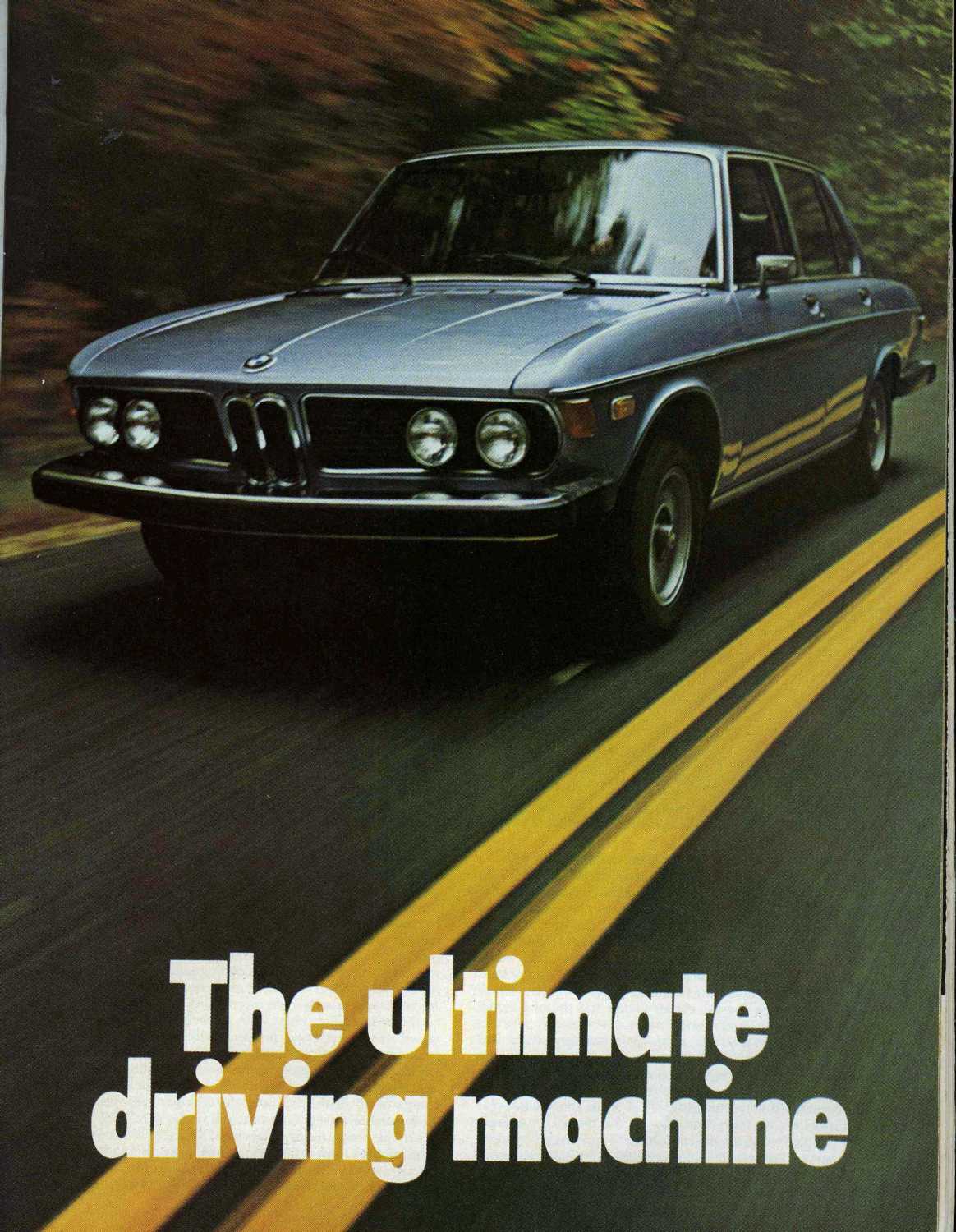

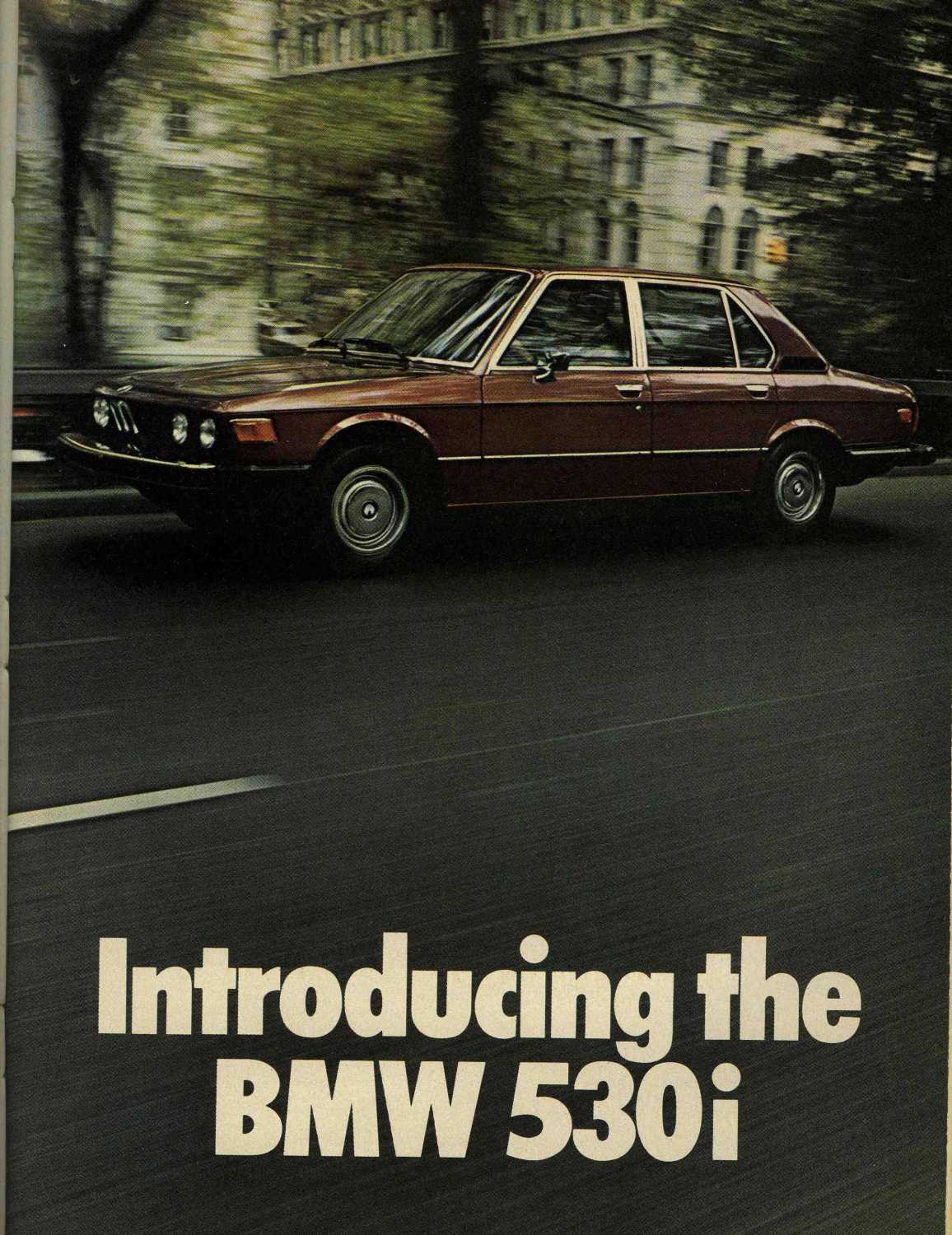

Before leaving BMW, Lutz had arranged for the BMW Motorsport team to race in the high-profile IMSA championship in 1975. On March 21, less than week after BMW NA had taken over from Hoffman, the 3.0 CSL scored its first IMSA win at Sebring. Lutz had also hired a new ad agency—Ammirati, Puris, AvRutick, later known as Ammirati & Puris—whose inspired “Ultimate Driving Machine” tagline was striking a chord with American enthusiasts.

“The branding was really taking hold,” McGurn said. “There was a story to be told, and the news media was printing the story.”

All of that, and the work of BMW of North America’s eager young employees, saw BMW more than triple its exports to the US during Cook’s tenure: from just 21,057 cars in 1975 to 62,501 cars in 1983. In 1984, Cook left BMW of North America to become a BMW dealer in Texas, but he returned to the corporate world a few years later to start Porsche Cars North America, another wholly-owned sales subsidiary. Cook died in 2004, age 76.

Max Hoffman, meanwhile, died in 1981, just six years after losing his BMW distributorship. He and his widow Marion had no children, but she created the Maximillian E. and Marion O. Hoffman Foundation to honor his memory. In 2023, the foundation had assets of $45.7 million and dispersed around $2 million to various charitable causes.

— ends —